What is a "dental cleaning"?

One of the most common ailments that I see affecting the quality of life of cats and dogs of all ages is periodontal disease. Preventing and treating periodontal disease can be tricky and relentless, but first we must understand what causes periodontal disease

Plaque and Tartar

Cats and dogs, much like humans, all have teeth which are always coated in a sticky biofilm called plaque. Plaque is composed of saliva, proteins, microbes, cells, and food debris. It sticks to the surface of teeth, in between teeth, as well as along and below the gumline. This plaque biofilm is what we aim to brush off twice daily when we brush our own teeth. If not brushed daily, plaque mixes with minerals in the saliva, creating tartar (also called calculus). Tartar cannot be removed by brushing alone - this is what we have scaled off when we go to the dentist for a “cleaning”.

Heavy tartar accumulation and gingivitis can be visualized

Xray of the above patient’s lower left premolars, showing advanced periodontal disease with bone loss and tooth resorption.

At a systemic level, periodontal disease persistently showers the bloodstream with bacteria, which are carried throughout the body creating a state of chronic inflammation. Over time these bacteria cause micro-abscesses in the liver and kidneys which negatively impacts their function. Bacteria in the bloodstream also make their way to the heart, where they attach to the heart valves, causing endocarditis.

What is a “dental cleaning”?

A professional “dental cleaning”, is now more accurately called a Complete Oral Health Assessment and Treatment. This is a medical procedure that involves the following steps:

Thorough discussion of patient history including current diet and oral hygiene routine.

Full physical examination in preparation for general anesthesia.

Pre-anesthetic diagnostics tailored to the pet’s needs.

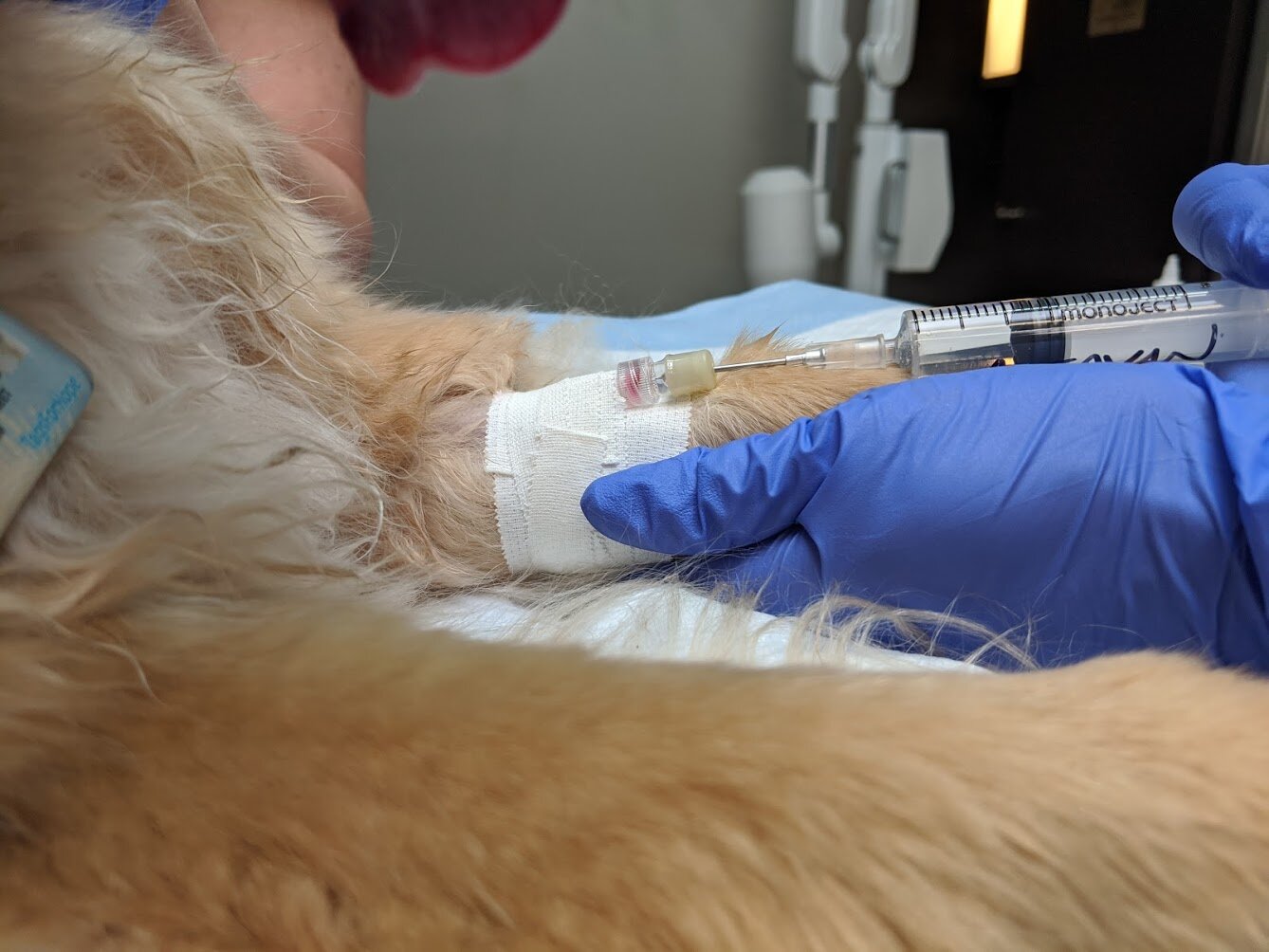

General anesthesia with continuous monitoring of vital parameters and multimodal pain control. This requires 2-3 staff members, including a veterinarian, a registered veterinary technologist, and a veterinary assistant.

Full-mouth dental Xrays: this allows us to examine the 60% of the tooth structure that is buried beneath the gumline as well as the surrounding bone.

Thorough oral cavity and dental examination which includes examination and probing of the crowns and pocket depths around each tooth. Results are recorded on a detailed chart of the oral cavity.

Teeth are scaled above and below the gumline to remove tartar.

If required, oral surgery is performed to extract any teeth with advanced/non-treatable periodontal disease and tissue biopsies obtained if needed.

Post-extraction Xrays to confirm complete extraction of each affected tooth.

Remaining teeth are polished above and below the gumline, then the oral cavity is rinsed.

Patient is monitored during recovery from anesthesia.

A progress visit is scheduled for 10-14 days after oral surgery to assess healing and to discuss an appropriate oral homecare.

This pictures captures the complexity of what is involved in a professional “cleaning” under general anesthesia.

What about anesthesia-free cleanings?

Anesthesia-free cleanings or non-professional dental scaling procedures are not only illegal across North America but are also considered malpractice for the following reasons:

Sharp hand instruments and ultrasonic power scalers are needed to remove mineralized tartar from tooth surfaces. Any movement of the pet while such instruments are in use in the oral cavity can result in injury to the patient and/or to the operator if the patient reacts with a bite.

The most critical part of scaling teeth is removing the plaque and tartar that has accumulated under the gumline, where periodontal disease is most active. Access to this subgingival space is not possible in an awake cat or dog. Removal of visible tartar on the tooth’s surface has little effect on the health of the pet and creates a false sense of accomplishment. Superficial scaling above the gumline is a cosmetic procedure only.

General anesthesia with a cuffed endotracheal tube allows for full cooperation of an animal for a procedure that it does not understand, eliminates any sensation of pain experienced during the procedure, and protects the airway and lungs from inhaling fluids required to thoroughly scale/polish the teeth.

A thorough oral and dental examination cannot be performed in an awake animal. Dental xrays, which require general anesthesia in pets, are needed to visualize most of the tooth structure and surrounding bone. We simply cannot know how healthy or not a tooth is without a picture of what lies under the gumline.

Pre-scaled image of a patient’s left dental arcades while it the patient is intubated and under general anesthesia

This Xray shows the full extent of an upper canine tooth. Most of the tooth structure in hidden under the gumline.

This one Xray shows some of the upper left premolars in the above patient. No extractions were required because these teeth are healthy above and below the gumline.

After a professional scale and polish under general anesthesia.

When periodontal disease goes unchecked

Although tartar contributes to inflammation and further plaque accumulation, it’s the plaque under the gumline that is most damaging. Bacteria under the gumline cause inflammation to gingival tissues (gingivitis) and release toxins that further damage periodontal tissues and the bone around a tooth’s root(s). With advanced periodontal disease, the teeth lose their attachment, causing painful tooth mobility and tooth root abscesses. Sometimes the bone loss around tooth roots is so advanced that the jaw can fracture - this is most common in older small/toy breed dogs.